Musical masterpiece journey with ethereal vocals and gold solid riddims inna dubwise fashion so COME ALONG!

Category: Dub Culture Department

Music, technology, science and wisdom of DuB culture.

Fearless & Far – Asking Tribal Elders Life’s Big Questions

Jah Billah says:

tek a listen.

In Jazz, Dub Is Everything Vol 1-5.

#Dub #Jazz

“In jazz, dub is everything” is mixtape series outta Novi Sad with yearly releases up on Mixcloud.

Full joy easy selection!

Haris Pilton meets Johnny Clarke & Hornsman Coyote – Dunza EP

#harispilton

Number one SloveniaJAH producer Haris Pilton coming in with Dunza EP featuring legendary Johny Clarke and Hornsman Coyote. Vocal and brass versions followed by 3 different dub cuts. NAH MISS!

“Dunza EP”

In a groundbreaking musical venture, Haris Pilton, the visionary artist and producer, is set to unveil his latest masterpiece, the ” Dunza EP.” This highly anticipated release sees the convergence of talents from various corners of the globe, creating a musical tapestry that transcends boundaries and genres. The EP, featuring the legendary Jamaican reggae singer Johnny Clarke and Serbia’s acclaimed trombone player Hornsman Coyote, is a testament to the universality of music and its power to connect diverse cultures.

Haris Pilton, known for his innovative approach to music production, has curated a collection of five tracks from the legendary Blood Dunza riddim. “Blood Dunza EP” is not just an EP album; it’s a sonic journey that invites listeners to immerse themselves in a world where tradition and modernity coalesce in perfect harmony.

The collaboration with Johnny Clarke, an icon in the Jamaican reggae scene, brings an authentic and timeless feel to the EP. Clarke’s soulful vocals and profound lyrics resonate throughout first song on EP, elevating the listening experience to new heights. His contribution adds a rich layer of authenticity to the project, making it a genuine celebration of reggae’s roots and golden era of reggae..

Hornsman Coyote, a maestro of the trombone hailing from Serbia, injects the EP with a distinct and vibrant energy. His skillful play weaves through the melodies, creating a bridge between the Caribbean rhythms and the soulful echoes of Eastern Europe. The result is a fusion that transcends borders, demonstrating the universal language of music.

As the mastermind behind the “Dunza EP,” Haris Pilton showcases not only his prowess as a producer but also his ability to bring together artists from different corners of the world. The EP is a testament to the power of collaboration and the magic that unfolds when diverse talents unite under a common creative vision.

With each track carefully crafted and produced by Haris Pilton, the “Dunza EP” promises a listening experience that is both captivating and thought-provoking. One vocal, one brass and three different dub versions from the roots-inspired beats to the contemporary twists, the EP encapsulates the essence of reggae while pushing the boundaries of the genre.

Prepare to embark on a musical odyssey as “Dunza EP” drops, inviting you to immerse yourself in the soulful & dubby sounds of reggae, enhanced by the collaborative brilliance of Haris Pilton, Johnny Clarke, and Hornsman Coyote. It’s more than an EP album; it’s a cultural convergence, a celebration of unity through music, and a testament to the enduring power of collaboration in the ever-evolving landscape of global soundscapes.

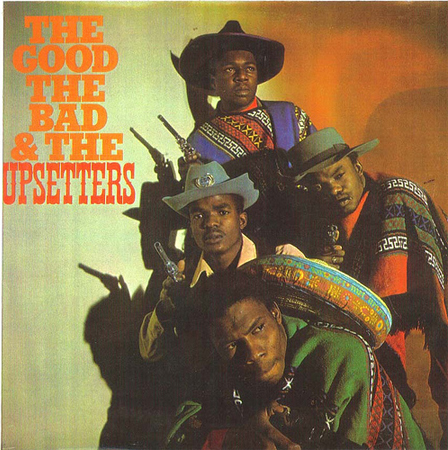

On ragga rude boy

#raggamuffin

Although Seaga‘s Jamaica, Thatcher‘s England, and Reagan‘s America gave ragga the kind of painful birth necessary for their mythic function, they really were always there. They were overshadowed by the spectacle of Rasta and its pious moralisms, but they were there nonetheless, stalking Jamaica’s neocolonial streets and consuming American cowboy and gangster films as well as the Old Testament and Pentecostalism.

They existed within Rasta from the moment it defined itself as an urban phenomenon and as a place for those suppressed by the hierarchical and color-stratified social structure of Jamaica.

During the sixties, before the hegemony of Rasta in the consciousness of ghetto sound, the earliest manifestation of the ragga can be located in the rude-boy phenomenon which swept the tiny island. The rudies, like today’s “gangbangers” in America, were young males who had little access to education and were victims of the incredible unemployment endemic to Third World urban centers. Their political consciousness was as developed as the Rastafari, but where the Rasta solution was one which often refused to engage directly with the harsh realities of ghetto and Third World life and frequently got lost in cloudy moments of rhetoric and myth (“roots and culture“), the rudies clung fiercely to “reality“-that trope central to today’s ragga/dancehall culture. They terrorized the island, modeling themselves after

their heroes from American films and glorying in their outlaw status. They killed, robbed, and looted, celebrating their very stylish nihilism. And ska and reggae – especially DJ-reggae, the beginning of rap/hip hop – were their musics.

Today the dreadlocks vision has been superseded-at least in the realm of sound and culture-by the rudie vision. The crucial differences between them can be seen quite vividly in their relationship to Babylon. Where in Rasta and other forms of popular Negritude there has always been some degree of nostalgia for a precolonial/preindustrial/precapitalist Africa, raggamuffin culture is very forward looking and capitalist oriented-as are most black people, despite the fantasies of many self-appointed nationalist leaders. These rudies focus their gaze, instead, on America, absorbing commodity culture from the fringes of the global marketplace, responding to it positively.

This means that in the context of a Third World ghetto where there are more guns per capita than anywhere else in the world, where legitimate employment is often a fantasy, where the drug trade and music provide the only available options for success, these young men find affirmation in the various messages that radiate out from America, an America that is not the “center” but rather an imagined source of transmission. Messages like The Godfather get picked up and translated into island style.

For example, one of the titles of utmost dancehall respect is “don.”

The raggamuffin pantheon is full of DJs with names like Clint Eastwood, Johnny Ringo, Al Capone, Josey Wales, and Dillinger; and today’s dons boast names like Bounty Killer, Shabba Ranks (named after a famous Jamaican gunman), and John Wayne. Also, the Jamaican underworld has always been full of characters who inscribed themselves into ghetto myth by renaming themselves in much the same way.

Male identity in this context is a necessary pastiche, and the allegorical representations of America’s dreams of itself become rewritten with a pen soaked in the blood of colonialism, slavery, and black ghet-to style. The gunfighter/outlaw image has always been there in reggae; it is now, however, without overt references to the Western world as the “Sheriff,” as in Bob Marley and the Wailers‘ classic “I Shot the Sheriff.”

For the ragga, this metaphor is no longer apt, for now they shoot each other in a lawless postcolonial terrain. Indeed, Ninjaman has described Jamaica as a “Cowboy Town.”

These names-and the notion of crime as political/cultural resistance that they signify – were there during Rasta‘s moment, but where the more Afrocentric embraced the Marley vision, the ghetto youth, the “bad-bwoys,” were smuggling in specialized weaponry like M16s, Glocks, and Bush-masters, killing each other and following their favorite sound systems around the island.

And, of course, the cocaine and marijuana trade was booming. In fact, it was booming in such a way that in the 1980s a few of the more enterprising Yardies invested some of this money which came to the ghetto in -believe it or not- state-of-the-art digital computer technology. Thus began what Jah Fish (Murray Elias), an avid follower of Jamaican music, has called the “the modem era” of Afro-Caribbean sound and culture.

Found in:

Post-Nationalist Geographies: Rasta, Ragga, and Reinventing Africa

Author: Louis Chude-Sokei

Source: African Arts, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Autumn, 1994),

Published by: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3337324

On cannabis in colonial Africa

#cannabis

Jah Billah says:

This article delineates pre-colonial and colonial use of cannabis in Africa. Starting with prehistoric cultivation 1300 BC in Ancient Egypt, and 2000 years ago in Madagascar. Going over North African and Sub-Saharan cannabis cultures, we learn that cannabis use was associated with coffee and that in Ethiopian language plant was once called esha tenbit “prophecy plant”. But what we choose to highlight here is documented use of tobacco as a colonial weapon against African cannabis cultures:

Cannabis Commerce and Legality

African cannabis markets were earliest documented in 13th-century Egypt, and 17th-century Southern Africa. Europeans widely observed commercial and exchange markets in all continental regions during the 1800s and early 1900s. In the Maghreb, 19th-century markets were highly formalized. By 1870, governments in precolonial Morocco and Ottoman Tunisia both began selling annual monopolies to their cannabis (and tobacco) trades. These monopolies continued under French rule until 1954.

European-controlled trades arose within colonial contexts and mostly supplied hard laborers. Three major trade regions existed, including the Maghreb. In South Africa, European merchants and settlers farmed and traded in cannabis from the late 1600s into the 1900s. Portuguese Mozambique also supplied South African laborers via exports to British Transvaal between 1908 and 1913. Miners were prominent consumers in colonial Southern and Central Africa. Finally, cannabis trades in western Central Africa included local traders stocking locally grown cannabis, as well as formal exports from Portuguese Angola to São Tome and Gabon during the 1870s to 1900s.

Even as these trades developed, colonial regimes increasingly suppressed cannabis. Rarely, colonial laws

rose upon indigenous prohibitions, as in Madagascar, where Merina royalty forbade cannabis by 1870,

decades before the French. Colonialists considered African cannabis an Eastern hindrance to Europe’s

civilizing mission. “The tobacco introduced by the Portuguese has contended successfully against the stupefying or maddening hemp […] from the far Muhammadan north-east,” told a British administrator in Belgian Congo in 1908.

Cannabis-control laws were enacted in Africa generally earlier than elsewhere worldwide, and were stricter too. Initial laws mostly aimed to improve public health, primarily by prohibiting behaviors considered detrimental to “native” health. Many laws clearly served ulterior motives, particularly labor control and religious proselytizing. British Natal’s 1870 law aimed to control Indian laborers, while Portuguese Angola’s 1913 law targeted colonial troops while also pushing farmers toward tobacco production. Cannabis was banned in most colonies by 1920. The plant drug first appeared in an international drug-control convention in 1925, based on the request of South Africa’s white minority government supported by newly independent Egypt, whose conservative authorities had suppressed cannabis since 1868 to control laborers.

Colonial authorities accepted and encouraged some drug crops—particularly tobacco, tea, and coffee—but cannabis was excluded, despite the existence (around 1840–1940) of an international market for Western pharmaceutical preparations of cannabis, supplied primarily from British India.

From:

Cannabis and Tobacco in Precolonial and Colonial Africa

Chris S. Duvall, 2017.

https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.44

Sensational VS Abu Ama

#sensational

If you don’t know by now step correct and re-frame Sensational of Crooklyn fame: subterranean lyrics over over lo fi dub noise beats, same as it ever was.

Originally grazing with Wordsound label, post apocalyptic illbient stable, alongside Bill Laswell rocking blue light torch of avant-garde hip hop and bass music since 1999, here comes Sensational VS Abu Amu with 2 tracks that don’t disappoint.

Yabass Yaba Radics – Year Zero Dubb

#yaba #yabass

Jah Billah says: don’t sleep on this 2020 classic, no sah!

If you don’t know Yabass, Alan ‘Yaba’ Blizzard, by now, time to know. Original UK sound from way back when you all had a smaller head.

I remember the original DUB ark at Versionist.com would rejoice when new Yabass DUB would drop cause they were heavyweight guaranteed.

Raw DUBness ahead!!!

Respectfully recommended for all DUB heads who nah miss out on that old haunting roots DUB Sound.

All instrument played with guests and mixed and recorded by Yaba himself.

Released on Hornin’ Sounds label outta France.

You can jump from easily selected Kunta Kinte version titled “Kinte Fights Pandemic” or start from the top to the very last drop.

Fulljoy sound of Yabass Guardian of the Underground!

On online collaborations

#HajiMike

Writing music online is nothing new. In 1994 ResRocket was the first online ‘band’ project with over 1,000 participants who exchanged ideas and files via a mailing list and ftp server.

By 1999 this had developed into one of the first live online music collaborations, screened on BBC TV in front of 55 million viewers. Bob Marley’s ‘Them Belly Full (but we hungry)’ was recorded live involving Sinead O’Connor, and Brinsley Forde in London, Thomas Dolby in San Francisco and Lucky Dube in South Africa.

While this marked a radical change in online music production it would take another few years before such creative collaborations would have more mass appeal from a production standpoint.

An obvious change came in radical developments in music production itself. The advent of more accessible and affordable Digital Audio Workstations (DAWs) which evolved from early pricey microprocessor based non-analogue tapeless systems, such as the Synclavier and Fairlight CMI to software such as DigiDesign’s Pro Tools, Logic Audio and Cubase ( the latter via the earlier pioneering Atari ST). Digitisation in more recent years has resulted in even cheaper or freeware options.

A PreSonus soundcard for example comes with a free version of the company’s own DAW software called Studio One (Presonus, 2010). Reaper from Cockos calls itself ‘Audio Production without limits’ and while it can be purchased the free evaluation copy functions in exactly the same manner (Reaper, 2010).

Simultaneously, The Internet itself has changed dramatically in terms of bandwidth, speed and accessibility. We have moved from archaic (by today’s standards) brick sized modems for the few who knew how to use binary computer code in the mid-1980’s to more compact modems with increased bandwidth and more recently DSL and fibre optic connections. Ten years ago it was possible to send a wav or aiff file online, it may have taken a few hours but now, it is much faster and easier, taking perhaps 10-15 minutes for say a 54 megabyte wav file. This is usually done through file transfer web sites such as ‘Sendspace’ and ‘Yousendit’. Many musicians now work together through their own ftp sites accessible with a username and password through their own web sites.

These advances have made a-synchronous music collaboration much more accessible to more people online in different locations around the world.

Fully synchronised collaboration exists as well, although this is usually subscriber based with a fee and requires substantial outbound bandwidth, often not accessible to as many people.

Examples of this include RiffWorks ( http://www.riffworld.com/) and NinJamm (http://ninjam.com/) although at times there are latency issues with both.

So although it is possible to link up studios in real time by using a service such as ‘source direct’ or an Avid Satellite link the cost of these options would be substantially high.

Synchronised music production online in different studios is still an emerging form of technology at least in terms of mass usage. It is likely, given rapid changes in technology that this may change through existing online communication tools, such as say Skype.

It is tempting at this point to view all these developments simply from a technologically deterministic standpoint, a view which one often finds in professional music production magazines which can be interpreted like a bunch of reviews on products, software and releases which exist in a kind of non-social world. I find such approaches based on technological determinism to be flawed from the outset as for me it is more important to understand how we can utilise various tools to create and make music through social engagement. The bottom line is not so much how the tools use us but how we use the tools and how these changes have had a sociological impact in interactive creative processes from symbolic and symbiotic points of view.

We have moved from a ‘sit-back-and-be-told culture’ to a ‘making-and-doing culture’. There are many social media web sites now which allow us to upload, share and exchange music, such as FaceBook, YouTube, Twitter, ReverbNation, Myspace, Soundcloud and Soundclick to name just a few. More niche oriented social media sites and web portals that specialize in particular forms of music and music scenes also exist. So people work within specific genres and across them. For example, Dubstep, The Dub Scrolls, BeatPort, and HipHop Makers. Through such sites, generic and niche, I found myself working online with people in Greece, Malta, Portugal, Sweden, UK, USA, and Cyprus.

The main reasons why I engaged in online musical collaboration was partly a frustration I had with studio based work, particularly being a spoken word based artist based in Cyprus making reggae, where many local studios and producers lack experience in these genres. I also entered into online collaborations by being approached by various people, who were more grounded in the kinds of music I engage in, to work with them online.

What appealed most to me was the openness of the Internet and the fact that it allowed users to explore so many different avenues in an accessible and democratic manner. Immediacy was also a major bonus. A song as I found out could be created, recorded, edited, mixed and mastered in different

places in say 24 hours. Additionally, various aspects of music production, distribution, promotion, and management became demystified. It became that much easier to make and share music with specific audiences via free social media web sites.

So independent net based labels, which Chuck D from Public Enemy dubbed as ‘Winties’ (web based independent labels) sprouted up in many countries around the world. The traditional filtering role played by radio and TV in the music industry in some ways became obsolete, after all much of the time they played only material that was signed to major labels and artists that had spent substantial amounts of money on their video clips. Now it is much easier to set up say a myspace account, upload some songs, live band footage, and gets known. Guerilla music making and self-marketing techniques are nothing new. They were deeply embedded in so many popular music scenes from punk rock to reggae. But the Internet suddenly gave that much more power to musicians to simply make, share and raise awareness of their existence. It is for example pointless and many people could also argue that it was from time, to send hundreds of cassettes or CD’s or vinyl demos out to record companies for consideration. Now an electronic press kit (EPK) could be assembled for free and sent to hundreds of targeted people with the click of a mouse.

Parts from Background – The Revolution has many interfaces! found in

By Mike Hajimichael aka Haji Mike, 2010.

On International Reggae and secularization of Rastafari 1972-1980

#rebelmusic #reggae #rasta

Ultimately, however, international reggae‘s appeal to international audiences may have had more to do with changes in the image of reggae artists, the packaging of the albums, and the sound of the music itself.

In his efforts to market the Wailers, for example, Blackwell first molded the Waiters‘ image into that of a rock-and-roll group. While reggae “groups” typically had consisted of a loose collection of singers and hired studio musicians, Blackwell promoted the Wailers as a stable, self-contained “band”—much like the Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin.

Second, Blackwell led a new trend among Jamaica’s record producers toward original, thematic, and full-length LP (long-play) albums, again following the lead of rock-and-roll groups. Previously Jamaica’s

record producers had distributed mostly singles or cheaply produced compilations of “greatest hits”.

Finally, those albums came packaged in glossy, well-produced jackets promoting the image of the rebellious, ganja-smoking Rastafarian. On the back cover of the Waiters‘ 1973 album Burnin‘, for example, Marley was pictured smoking a 12-inch spliff, or marijuana cigarette. On Peter Tosh‘s 1976 album, Legalize It, the singer was photographed crouched down in a ganja field. Reggae album covers also emphasized the Rastafarian’s symbol of black defiance, the dreadlocks, or displayed the Ethiopian colors of red, green, and gold. The cover of the Wailers‘ 1980 album Uprising, for example, featured a drawing of Bob Marley, along with the album’s title in red, and a background of green mountains

and a gold sun.

While most of the major instrumental innovations of international reggae were established during the early reggae period, international reggae was marked by a more sophisticated and polished studio sound. Most early reggae songs were recorded in primitive studios in Jamaica. International reggae, however, generally was recorded in state-of-the-art studios in the United States or Great Britain.

According to Jones, this helped to undermine “the common accusation made by rock fans that reggae was a music of ‘inferior’ quality”. In the first attempt to reverse this trend, Chris Blackwell took the Wailers‘ instrumental tracks for Catch a Fire, previously recorded in Jamaica, and remixed, edited, and mastered the tracks in a London studio.

Rock critics Ed Ward, Geoffrey Stokes, and Ken Tucker highlighted the dramatic change in reggae’s new sound: “Catch a Fire” was a “revolutionary example of reggae recording, far superior in its technology than most other reggae records”.

U.S. and British record producers also manipulated the instrumentation in reggae arrangements to create a lighter, “softer” reggae. Some U.S. record producers would deemphasize reggae’s dominant instruments, the electric bass guitar and drums, and push the keyboard and electric guitar to the front of the mix. In 1980, Jamaican dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson provided a clear rationale for the systematic manipulation of the reggae sound:

“[there was the] belief that the hard Jamaican sound, with the emphasis on the drum and the bass, would not be as accessible to the non-Jamaican listener as a lighter sounding production would be”.

To appeal to international audiences, reggae musicians also incorporated familiar genres of American music into the reggae arrangement.

During the remixing of the Wailers‘ Catch a Fire, for example, Blackwell dubbed traditional rock-and-roll instruments, including rock guitar and synthesizer, over the reggae beat. During the recording of

the same album, a session guitarist, Wayne Perkins, also added guitar solos. Throughout their career, the Wailers dabbled in blues (“Talkin’ Blues” [Natty Dread]), funk (“Is This Love?” [Kaya]), and folk music

(“Redemption Song” [Uprising]). Similarly, Toots and the Maytals, in their 1973 Funky Kingston, fused R&B and reggae into the album’s title song.

In sum, the new international success of reggae music in the 1970s may have been more the result of marketing and changes in its sound than changes in its “message.” Reggae was still a “rebel music.” Growing up in some of Jamaica’s worst slums, reggae musicians still critiqued Jamaica’s neocolonial society. Reggae musicians also expressed concern about international affairs, specifically political problems on the African continent. While still sensitive to the problems at home, they also began

to identify themselves more as Africans than Jamaicans. In the final analysis, however, reggae’s international success probably was more the result of changes in its sound. Record producers improved and “softened” the reggae sound and incorporated new instruments, such as synthesizers and rock guitars, into the reggae arrangement.

Reggae musicians also borrowed freely from musical genres including rhythm and blues and funk. Yet whatever the explanation, reggae’s sudden status as an international musical sensation focused unprecedented attention on the Rastafarian movement and exacerbated tensions within the move-ment. Indeed, the music created whole new groups of supposed Rastafarians apparently attracted to the movement by little more than the image of the “Rastaman” and the music itself. These “pseudo” Rastafarians had little in common with traditional Rastafarian principles and beliefs.

Parts of Chapter Reggae Music in the 1970s: “Bubbling on the Top 100” from:

Stephen A. King (1998) International reggae, democratic socialism, and the secularization of the Rastafarian movement, 1972–1980, Popular Music and Society, 22:3, 39-60,

DOI: 10.1080/03007769808591713

On Rasta continuum in Cuba

#rasta #style #Cuba

Real versus fake Rastas

Not unlike in many other Rasta communities around the world some of the more conservative religious brethren have introduced a view and language of authenticity with regards to what it means to be a Rasta. Framed in a discourse of cultural purity, they speak of so-called "real" and "unreal or “fake" Rastas. But, given the myriad of ways people in Cuba identify with and express Rastafari, who can be considered a “real” Rasta?

The aim of my research has precisely been to go beyond fixed ideas of what constitutes a Rasta and instead look at how and why people define themselves as such and what processes go into making that

identity. Apart from this all-inclusive approach, the movement’s own fragmented entrance into Cuba and the many ways in which it has been appropriated have led to the wide array of definitions and expressions of the movement.

Although I have grouped certain main characteristics together and created certain "types" of Rastas for analytical purposes, in actuality every individual has his/her own idiosyncratic understanding and way of manifesting Rastafari. Ulf Hannerz’s views on the social organisation of culture are particularly helpful in understanding Rastafari’s heterogeneous character in Cuba: The social organisation of culture always depends both on the communicative flow and on the differentiation of experiences and interests in society. In the complex society, the latter differentiation is by definition considerable. It also tends to have a more uneven communicative flow - that is, different messages reach different people. The combined effect of both the uneven flow of communications and the diversity of experiences and interests is a differentiation of perspectives among the members of the society.

Rastafari in Cuba has been localised in just such a fashion. In an almost consumer-like attitude towards culture, individuals have selectively chosen, imitated and modified Rasta elements as well as mixed and matched them with other cultural practices. Whilst some have thus consciously hybridised different cultural elements together, others have kept them consciously apart by way of “cultural crossing” or “milieu-moving". Others yet again have adopted what Swidler (1986) has referred to as a “toolkit” attitude towards culture, in which people engage in their everyday activities by “selecting certain cultural elements (both such tacit culture as attitudes and styles and, sometimes, such explicit cultural materials as rituals and beliefs) and investing them with particular meanings in concrete life circumstances“.

In illustrating their skills at maintaining, mixing and serially selecting facets of different lifeways and styles all Rastas have demonstrated a high degree of multiple cultural competence as well as an attachment to a multiplicity of identities. In addition, all Cuban Rastas, even those who insist on an ideology of purity, have to a greater or lesser extent juxtaposed and fused objects, symbols and signifying practices from different and separate domains and in so doing have produced new, creolised versions of Rastafari.

On the whole, what we thus find is a wide variety of identifications with the movement, which can perhaps best be described as a Rasta continuum, ranging from orthodox religious brethren and sistren to those who identify with Rasta as a style. This same continuum is in addition in constant flux as individuals engage in an ongoing process of learning, adding, copying and reinterpreting Rastafari symbols and doctrine. As a cultural phenomenon Rastafari can be said to be in a constant state of cubanisation.

Chapter from:

Katrin Hansing (2001) Rasta, race and revolution: Transnational

connections in socialist Cuba, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 27:4, 733-747,

DOI:10.1080/13691830120090476