#raggamuffin

Although Seaga‘s Jamaica, Thatcher‘s England, and Reagan‘s America gave ragga the kind of painful birth necessary for their mythic function, they really were always there. They were overshadowed by the spectacle of Rasta and its pious moralisms, but they were there nonetheless, stalking Jamaica’s neocolonial streets and consuming American cowboy and gangster films as well as the Old Testament and Pentecostalism.

They existed within Rasta from the moment it defined itself as an urban phenomenon and as a place for those suppressed by the hierarchical and color-stratified social structure of Jamaica.

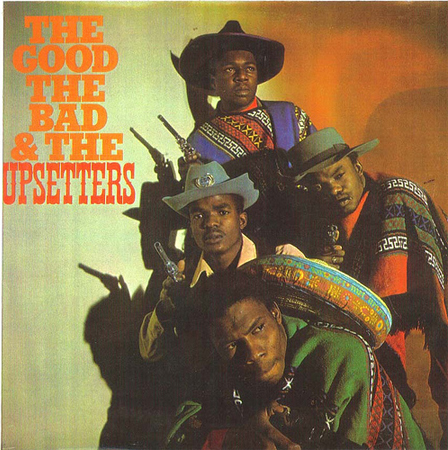

During the sixties, before the hegemony of Rasta in the consciousness of ghetto sound, the earliest manifestation of the ragga can be located in the rude-boy phenomenon which swept the tiny island. The rudies, like today’s “gangbangers” in America, were young males who had little access to education and were victims of the incredible unemployment endemic to Third World urban centers. Their political consciousness was as developed as the Rastafari, but where the Rasta solution was one which often refused to engage directly with the harsh realities of ghetto and Third World life and frequently got lost in cloudy moments of rhetoric and myth (“roots and culture“), the rudies clung fiercely to “reality“-that trope central to today’s ragga/dancehall culture. They terrorized the island, modeling themselves after

their heroes from American films and glorying in their outlaw status. They killed, robbed, and looted, celebrating their very stylish nihilism. And ska and reggae – especially DJ-reggae, the beginning of rap/hip hop – were their musics.

Today the dreadlocks vision has been superseded-at least in the realm of sound and culture-by the rudie vision. The crucial differences between them can be seen quite vividly in their relationship to Babylon. Where in Rasta and other forms of popular Negritude there has always been some degree of nostalgia for a precolonial/preindustrial/precapitalist Africa, raggamuffin culture is very forward looking and capitalist oriented-as are most black people, despite the fantasies of many self-appointed nationalist leaders. These rudies focus their gaze, instead, on America, absorbing commodity culture from the fringes of the global marketplace, responding to it positively.

This means that in the context of a Third World ghetto where there are more guns per capita than anywhere else in the world, where legitimate employment is often a fantasy, where the drug trade and music provide the only available options for success, these young men find affirmation in the various messages that radiate out from America, an America that is not the “center” but rather an imagined source of transmission. Messages like The Godfather get picked up and translated into island style.

For example, one of the titles of utmost dancehall respect is “don.”

The raggamuffin pantheon is full of DJs with names like Clint Eastwood, Johnny Ringo, Al Capone, Josey Wales, and Dillinger; and today’s dons boast names like Bounty Killer, Shabba Ranks (named after a famous Jamaican gunman), and John Wayne. Also, the Jamaican underworld has always been full of characters who inscribed themselves into ghetto myth by renaming themselves in much the same way.

Male identity in this context is a necessary pastiche, and the allegorical representations of America’s dreams of itself become rewritten with a pen soaked in the blood of colonialism, slavery, and black ghet-to style. The gunfighter/outlaw image has always been there in reggae; it is now, however, without overt references to the Western world as the “Sheriff,” as in Bob Marley and the Wailers‘ classic “I Shot the Sheriff.”

For the ragga, this metaphor is no longer apt, for now they shoot each other in a lawless postcolonial terrain. Indeed, Ninjaman has described Jamaica as a “Cowboy Town.”

These names-and the notion of crime as political/cultural resistance that they signify – were there during Rasta‘s moment, but where the more Afrocentric embraced the Marley vision, the ghetto youth, the “bad-bwoys,” were smuggling in specialized weaponry like M16s, Glocks, and Bush-masters, killing each other and following their favorite sound systems around the island.

And, of course, the cocaine and marijuana trade was booming. In fact, it was booming in such a way that in the 1980s a few of the more enterprising Yardies invested some of this money which came to the ghetto in -believe it or not- state-of-the-art digital computer technology. Thus began what Jah Fish (Murray Elias), an avid follower of Jamaican music, has called the “the modem era” of Afro-Caribbean sound and culture.

Found in:

Post-Nationalist Geographies: Rasta, Ragga, and Reinventing Africa

Author: Louis Chude-Sokei

Source: African Arts, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Autumn, 1994),

Published by: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3337324