#rebelmusic #reggae #rasta

Ultimately, however, international reggae‘s appeal to international audiences may have had more to do with changes in the image of reggae artists, the packaging of the albums, and the sound of the music itself.

In his efforts to market the Wailers, for example, Blackwell first molded the Waiters‘ image into that of a rock-and-roll group. While reggae “groups” typically had consisted of a loose collection of singers and hired studio musicians, Blackwell promoted the Wailers as a stable, self-contained “band”—much like the Rolling Stones or Led Zeppelin.

Second, Blackwell led a new trend among Jamaica’s record producers toward original, thematic, and full-length LP (long-play) albums, again following the lead of rock-and-roll groups. Previously Jamaica’s

record producers had distributed mostly singles or cheaply produced compilations of “greatest hits”.

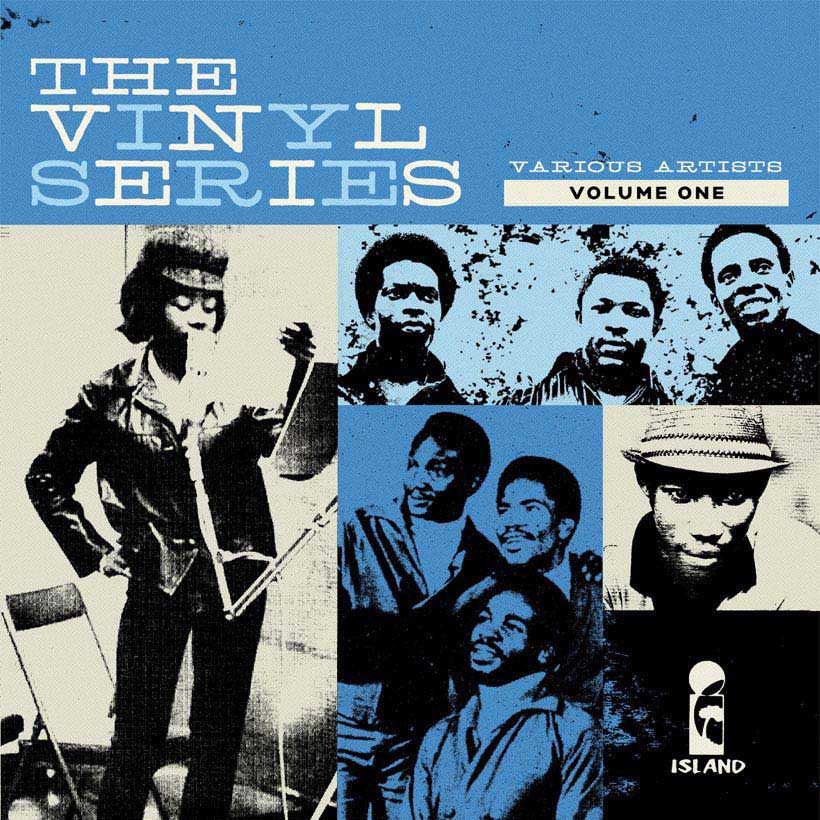

Finally, those albums came packaged in glossy, well-produced jackets promoting the image of the rebellious, ganja-smoking Rastafarian. On the back cover of the Waiters‘ 1973 album Burnin‘, for example, Marley was pictured smoking a 12-inch spliff, or marijuana cigarette. On Peter Tosh‘s 1976 album, Legalize It, the singer was photographed crouched down in a ganja field. Reggae album covers also emphasized the Rastafarian’s symbol of black defiance, the dreadlocks, or displayed the Ethiopian colors of red, green, and gold. The cover of the Wailers‘ 1980 album Uprising, for example, featured a drawing of Bob Marley, along with the album’s title in red, and a background of green mountains

and a gold sun.

While most of the major instrumental innovations of international reggae were established during the early reggae period, international reggae was marked by a more sophisticated and polished studio sound. Most early reggae songs were recorded in primitive studios in Jamaica. International reggae, however, generally was recorded in state-of-the-art studios in the United States or Great Britain.

According to Jones, this helped to undermine “the common accusation made by rock fans that reggae was a music of ‘inferior’ quality”. In the first attempt to reverse this trend, Chris Blackwell took the Wailers‘ instrumental tracks for Catch a Fire, previously recorded in Jamaica, and remixed, edited, and mastered the tracks in a London studio.

Rock critics Ed Ward, Geoffrey Stokes, and Ken Tucker highlighted the dramatic change in reggae’s new sound: “Catch a Fire” was a “revolutionary example of reggae recording, far superior in its technology than most other reggae records”.

U.S. and British record producers also manipulated the instrumentation in reggae arrangements to create a lighter, “softer” reggae. Some U.S. record producers would deemphasize reggae’s dominant instruments, the electric bass guitar and drums, and push the keyboard and electric guitar to the front of the mix. In 1980, Jamaican dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson provided a clear rationale for the systematic manipulation of the reggae sound:

“[there was the] belief that the hard Jamaican sound, with the emphasis on the drum and the bass, would not be as accessible to the non-Jamaican listener as a lighter sounding production would be”.

To appeal to international audiences, reggae musicians also incorporated familiar genres of American music into the reggae arrangement.

During the remixing of the Wailers‘ Catch a Fire, for example, Blackwell dubbed traditional rock-and-roll instruments, including rock guitar and synthesizer, over the reggae beat. During the recording of

the same album, a session guitarist, Wayne Perkins, also added guitar solos. Throughout their career, the Wailers dabbled in blues (“Talkin’ Blues” [Natty Dread]), funk (“Is This Love?” [Kaya]), and folk music

(“Redemption Song” [Uprising]). Similarly, Toots and the Maytals, in their 1973 Funky Kingston, fused R&B and reggae into the album’s title song.

In sum, the new international success of reggae music in the 1970s may have been more the result of marketing and changes in its sound than changes in its “message.” Reggae was still a “rebel music.” Growing up in some of Jamaica’s worst slums, reggae musicians still critiqued Jamaica’s neocolonial society. Reggae musicians also expressed concern about international affairs, specifically political problems on the African continent. While still sensitive to the problems at home, they also began

to identify themselves more as Africans than Jamaicans. In the final analysis, however, reggae’s international success probably was more the result of changes in its sound. Record producers improved and “softened” the reggae sound and incorporated new instruments, such as synthesizers and rock guitars, into the reggae arrangement.

Reggae musicians also borrowed freely from musical genres including rhythm and blues and funk. Yet whatever the explanation, reggae’s sudden status as an international musical sensation focused unprecedented attention on the Rastafarian movement and exacerbated tensions within the move-ment. Indeed, the music created whole new groups of supposed Rastafarians apparently attracted to the movement by little more than the image of the “Rastaman” and the music itself. These “pseudo” Rastafarians had little in common with traditional Rastafarian principles and beliefs.

Parts of Chapter Reggae Music in the 1970s: “Bubbling on the Top 100” from:

Stephen A. King (1998) International reggae, democratic socialism, and the secularization of the Rastafarian movement, 1972–1980, Popular Music and Society, 22:3, 39-60,

DOI: 10.1080/03007769808591713